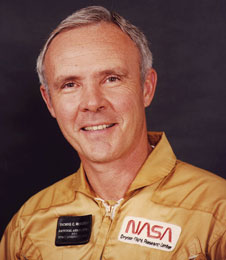

Thomas C. McMurtry was respected by peers, admired for his piloting skills and appreciated for his mentoring by many who knew him. The retired NASA Armstrong Flight Research Center research pilot died Jan. 3. He was 79.

Thomas C. McMurtry was respected by peers, admired for his piloting skills and appreciated for his mentoring by many who knew him. The retired NASA Armstrong Flight Research Center research pilot died Jan. 3. He was 79.

He is known for his exploits behind the stick of such aircraft as the triple-sonic YF-12C, the U-2 and F-104 aircraft during a career that included more than 15,000 hours. This number includes 4,000 hours recorded while flying for two private aviation firms for 12 years after his retirement from NASA.

McMurtry joined the NASA Flight Research Center (now NASA Armstrong) in 1967 after service as a U.S. Navy pilot and with the Lockheed Corporation. He was a project pilot on some of the most significant flight research projects in the center’s history during his 32-year tenure, including the AD-1 oblique wing project, the F-15 Digital Electronic Engine Control project, the KC-135 winglets study and the F-8 Supercritical Wing project for which he received NASA’s Exceptional Service Medal.

He also served as co-project pilot on a number of other flight research projects, including the F-8 Digital Fly-By-Wire project and the X-24B lifting body. McMurtry also flew one of the two modified NASA 747 Shuttle Carrier Aircraft, or SCA, that ferried space shuttles from Edwards Air Force Base California to Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

Fitz Fulton, a retired NASA pilot, fondly recalled working with McMurtry.

“I was close to him for 20 years as we flew projects together, he was my boss part of the time,” Fulton said. “He could not have been a nicer boss. He was very mild mannered, but when the tough gets going he could be tough. He also was an excellent athlete.”

Fulton and McMurtry shared duties on the space shuttle ferry flights that usually included a few stops dictated by weather along the route. The two men were part of a small number of pilots that were qualified to fly the NASA 747 SCA.

Bill Brockett, a longtime NASA pilot, flew missions of the Kuiper Airborne Observatory, the precursor to the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy, with McMurtry at the NASA Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California. Brockett also came to NASA Dryden (now Armstrong) as a result of McMurtry’s prompting.

“It’s difficult to think about him without going to superlatives,” Brockett said. ” He was one-of-a kind, polite and well spoken. He was rock solid and steady as anybody I ever met. The first thing that struck me was his big smile and how all the young Air Force guys marveled at meeting him. “

When Brockett was going to retire from NASA in the late 1990s, McMurtry factored into the decision.

“I was going to retire from NASA and go back to industry to become an airline pilot,” Brockett said. “Six weeks before retirement I received an e-mail from Tom and an offer to assist me with references. I responded that I really enjoyed working with him and only regret was never having taken him up on an offer to go on an F/A-18 ride.”

A week before he retired, McMurtry asked former NASA astronaut and then Dryden pilot Gordon Fullerton to fulfill Brockett’s request. A flight with Gordo was enough to change Brockett’s mind.

“By the end of flight I realized that I really wanted to stay with NASA and not go back to airline flying. I went in an entirely different direction because McMurtry completely changed my mind.

“I view him as a father figure and a symbol of the right way to live your life. He exemplified all of the finest values of honesty and integrity and properness and cheerfulness.”

Brockett also recounted a McMurtry F-104N flight that didn’t go as planned.

“On an F-104 mission when McMurtry chased the NASA B-52 that was to drop Bill Dana in the M2-F3 lifting body aircraft during a test mission over the lakebed,” Brockett recalled a story McMurtry told him.” He was to fly safety chase. The F-104 was close to stalling to stay slow enough to stay behind the lifting body and monitor flight control positions. About the time of release of the lifting body, McMurtry stalled and the aircraft went into a spin.

“The lifting body was flying, but everyone was riveted on the F-104 in a spin. The aircraft were notoriously hard to pull out. He had tried three recovery attempts. Then he tried once more and this time the aircraft’s nose dropped low enough that the F-104 came out of the spin right in position at the wing of the lifting body and flew through the mission as if nothing had happened. McMurtry said, ‘It would have been really embarrassing if I had to eject on a chase flight.'”

Bradley Flick, NASA Armstrong director for Research and Engineering, recalled working for McMurtry as a young operations engineer.

“While Tom was not formally a mentor to me, I enjoyed a very good, open relationship with him and often sought his guidance on problems,” Flick said. “His calm demeanor and sage advice always took me to the right decision and left me with an increased sense of confidence in myself.”

Early in his career at NASA Armstrong, Flick had an engineering responsibility on the F/A-18 High Alpha Research Vehicle. He also was occasionally asked to weigh in on the F/A-18 support aircraft. The pre-production aircraft had a number of systems challenges, some of which were often unrepeatable.

“I was often one of the guys who had to explain what was going on to Tom, who had to agree that it was OK to fly with some potentially latent deficiencies. He always asked the right questions to understand just how much risk we were taking. It wasn’t until much later in my career that I recognized the level of trust that Tom and other center leaders were placing in me and that each of those conversations was a bit of test. That’s very humbling in hindsight and I try to challenge myself to conduct myself similarly.”

McMurtry also inspired SOFIA Program Manager Eddie Zavala, who as a Texas A&M engineering student attended a presentation at which McMurtry was a keynote speaker.

“Afterward I approached McMurtry and right off the bat he encouraged me to apply for a cooperative education position at Dryden (now NASA Armstrong). It was quite remarkable because he said based on my interests that Dryden would be a really good fit for me. He explained how what the center did matched what I wanted to do. Other recruiters were much more interested in what I could offer them. That was the start of his informal mentorship with me.”

After three cooperative education sessions at Dryden, Zavala became a permanent employee. He thanked McMurtry a few years ago for his encouragement to come to Dryden and continuing his encouragement at times when Zavala really needed it.

“He was always looking to encourage and promote others. He never sought the spotlight for himself. He led by example,” Zavala said.

The Federal Aviation Administration honored McMurtry in October with the presentation of the agency’s Wright Brothers Master Pilot Award during a ceremony in Palmdale.

McMurtry, whose activity was severely limited following a debilitating stroke, was also presented with resolutions and certificates honoring his service to NASA and the nation from several public officials.

More information on Tom McMurtry’s life and career is available here.