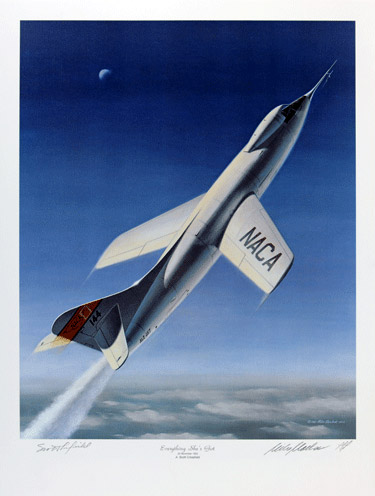

By Mike Machat, July 2006 Airpower magazine

By Mike Machat, July 2006 Airpower magazine

“The Skyrocket gave everything she had”. Sitting across from me at the Wings Club in Washington DC that day in 1986 was former NACA test pilot Scott Crossfield, known as ‘Scotty’ to his friends and ‘Mr. Crossfield’ to others, but above all, the first man to fly an aircraft at twice the speed of sound, and the first man to fly the hypersonic North American X-15 rocketplane. At that time, we were collaborating on a project in which I was to produce a painting depicting his historic Mach 2 flight in the Douglas D-558-II research craft in November 1953. Purchase this art print.

He recounted that day how his hand had frozen to the stick at altitude because he‘d wanted to feel every nuance of the Skyrocket in flight, and chose not to wear gloves. We talked enthusiastically about the ‘Golden Age’ at Edwards and it was here that I first learned what a true gentleman Scott Crossfield really was.

D-558-2 Scott Crossfield launch from B-29.

The subject of Chuck Yeager came up in conversation, and in one concise sentence Crossfield neatly dispelled all the celebrated media hype about his supposed rivalry with the famed Air Force test pilot.

“Charlie was the best. If it had been anyone else flying the X-1A”, Crossfield commented, remembering Yeager’s tumultuous Mach 2.5 flight in December 1953, “they never would have made it back.”

In the years following that encounter, I’d heard Crossfield speak on numerous occasions. Articulate, erudite, and with a sharp wit just shy of a 1950’s Borscht Belt comedian, Scott would hold a roomful of adoring fans spellbound with stories of everything from his exploits as a Navy pilot instructing in SNJs and flying SBDs, Hellcats, and Corsairs during World War II to his pioneering proving flights in North American’s revolutionary black mantis, the X-15. When thinking of a person who exemplified the words ‘scholar’, ‘character’, and ‘integrity’ in aviation, it was Crossfield who first came to mind.

An aerodynamicist and aeronautical engineer by trade and a dedicated and thorough research pilot by avocation, Scott Crossfield brought his unique style and persona to any number of aviation challenges. He joined the fledgling National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics (NACA, predecessor to NASA) in June 1950 and soon established himself as one of the rare breed of men known as the ‘rocket pilots’.

First glide flight of X-15 with pilot Scott Crossfield.

Flying such aeronautical thoroughbreds as the Bell X-1 and Douglas D-558-II, Crossfield built up a solid block of rocket-propelled flight time probing the frontiers of high speed and high altitude flight. On November 20, 1953, he pushed the Douglas Skyrocket to its absolute limits, achieving a record speed of Mach 2.005 (1,320 mph) and entering the history books as ‘the first man to fly at twice the speed of sound’.

Crossfield also accumulated flight time in a host of other exotic research aircraft such as the transonic Douglas D-558-I Skystreak, tailless Northrop X-4 Bantam, swing-wing Bell X-5, delta-wing Convair XF-92 and supersonic North American F-100. It was in the Super Sabre that Crossfield gained fame of sorts for surviving an incident that could’ve ended in tragedy. While coasting to a stop on the NASA ramp at Edwards taxiing in after a test flight, Scotty discovered that he’d lost hydraulic pressure and was thus without any braking action whatsoever. It was only the side of the hangar that stopped the errant aircraft, prompting the always self-effacing Crossfield to later quip “The sonic wall was Yeager’s, the hangar wall was mine.”

Scott Crossfield flying the X15 to Mach 3

Leaving a promising career with NASA, Crossfield made the transition from government agency test pilot to private sector design engineer by joining North American Aviation Corporation and becoming Lead Engineering Test Pilot on the new X-15 program, dedicating his life at that time to the successful design and development of the world’s first airplane to be able to fly into space and then return to a precision landing at a pre-determined site.

Making the first glide and powered flights in 1959, Scott racked up a total of 14 X-15 missions amidst countless frustrating aborts, one crash landing, and a near-catastrophic explosion during a rocket engine ground test. His efforts were instrumental in the ultimate success of that legendary test program, a record-breaking effort that literally paved the way for the Space Shuttle. Oddly enough, when asked to recount his exploits in the X-15, Crossfield would become almost gruff in his reply, pointedly asking the unsuspecting interviewer why we haven’t done anything better than what was accomplished during his test flights of a half-century ago.

Scott Crossfield makes emergency landing in X-15 on 5 November 1959

As a reliability and systems engineer for North American during the Apollo Program, Crossfield was involved with not only taking the first embryonic steps towards manned space flight, but in sending manned spacecraft to the Moon and returning them safely to Earth – an effort that ended more than 30 years ago. “We should be looking forward, not back”, was his constant lament. Some would call him cantankerous, others would call him irascible. He would be more properly known as ‘a futurist’.

Born October 2, 1921, Albert Scott Crossfield dedicated his life to making the world a better place through aviation progress. Decorated in later years with every possible award from the Collier Trophy to being inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame, he represented the epitome of an engineering test pilot who could translate hard data from the drawing board into advanced performance during flight test.

North American Aviation coverage of X-15 flight test program including the record making flights of Scott Crossfield, Maj. Robert White, Joseph Walker, Cmdr. Peterson, Jack McKay, Capt. Rushworth, and Neil Armstrong..

Sadly, on April 19, 2006, Scott Crossfield died in the crash of his Cessna 210A while encountering a severe thunderstorm enroute from Montgomery, Alabama to his home field of Manassas, Virginia. He was returning home after addressing Air Force students at the Air Command and Staff College at Maxwell AFB – fittingly sharing his views of aviation history through the eyes of someone who lived it.