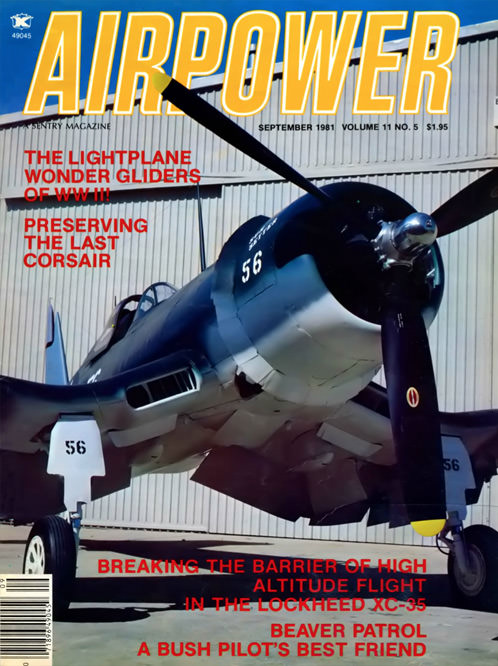

A First Hand Account on the Restoration of an F4U Corsair That Will Endure For Centuries, by the Curator of Aircraft at the National Air & Space Museum.

By Robert C. Mikesh, September 1981 edition of Airpower

Expected to one day become the sole survivor of this breed of aircraft, a Vought F4U-1D Corsair has recently been restored and preserved by the National Air and Space Museum, in Washington, D.C. This might sound like an overly confident prediction to make at this early stage when nearly a squadron’s strength of Corsairs are still flying, and almost two dozen more, including postwar built models, reside in museums throughout the world. But time will take its toll and, one by one, the airworthy machines will be stricken. Internal corrosion will relentlessly eat away at those on the ground, and it is safe to assume that the greater portion of those that have survived to the present will no longer be around to be seen and enjoyed by the next generation.

Expected to one day become the sole survivor of this breed of aircraft, a Vought F4U-1D Corsair has recently been restored and preserved by the National Air and Space Museum, in Washington, D.C. This might sound like an overly confident prediction to make at this early stage when nearly a squadron’s strength of Corsairs are still flying, and almost two dozen more, including postwar built models, reside in museums throughout the world. But time will take its toll and, one by one, the airworthy machines will be stricken. Internal corrosion will relentlessly eat away at those on the ground, and it is safe to assume that the greater portion of those that have survived to the present will no longer be around to be seen and enjoyed by the next generation.

At the National Air and Space Museum, the future is prepared for today. When a restoration is undertaken, it is done for the purpose of preserving aircraft indefinitely. Each component, every crevice and the entire surface of the machine is cleaned of corrosion and given a protective coating with the intent of preserving the aircraft for centuries.

We aviation enthusiasts are a fortunate group. It has been a mere eighty years since the development of man-carrying aircraft, yet some of these very early aircraft are still with us today. Nearly any form of aircraft structural material will last a century, but it must be given the proper care. Even World War II aircraft that have been abused by weather in outdoor exhibits or abandoned in junkyards can be saved, but the fact is just now beginning to be realized by the more professional museums that greater care must be given to the aircraft at hand while there is enough of their time-eroded structure still intact.

The Museum’s Corsair is one of these airplanes, and the story surrounding its restoration and special processing for preservation is a fascinating one. In some museum circles, this process is termed a “conversion.” That is: To take an airplane which was manufactured to only survive for its expected operational lifetime and give it special safeguards to retard its natural rate of deterioration so that its life can be extended indefinitely. In short, transform it from a functional machine to a static display. This does not necessarily mean that the airplane could not be made flyable again should that need arise, but to do so would initiate once again the process of progressive deterioration.

Our particular Corsair came to the museum collection, as did so many of the other World War II aircraft, after hostilities had ceased. When the war ended, General of the Army Air Forces, H.H. Arnold, directed that one of each military aircraft type, including foreign aircraft possessed by the Army, be set aside for future educational purposes and preserved in a museum. He encouraged the U.S. Navy to do likewise. In this regard, a Navy collection was gathered at NAS Norfolk, which included this Corsair along with many other Navy types. In 1960, most of the Navy’s aircraft were moved by barge to the Washington Navy Yard and then taken by road to the Museum’s storage facility at Silver Hill, Maryland, renamed in June 1980 as the Paul E. Garber Preservation, Restoration and Storage Facility. It was Garber, now Historian Emeritus, who for sixty years looked after the collection of aircraft and continually sought out and procured the many historical airplanes that now grace the Museum’s halls.

Taking a closer look at this Corsair, BuNo. 50375, its records reveal that it had a rather significant historical background. It was delivered to the Navy from its Stratford, Connecticut factory on April 26, 1944, to an unrecorded destination. By October, it was carried as being assigned to VF-1 0 and a month later to VF-89, both Navy fighter squadrons. This latter outfit was newly commissioned on October 2, 1944, and was being equipped at NAS Atlantic City. This Corsair remained with that unit until February 1945, through unit moves to NAS Oceana and NAS Norfolk. There it was assigned to await installation of an undescribed “beacon” system, according to its service record card. From Norfolk, it was moved to Quantico Marine Air Station on June 30, 1945, to join the surplus aircraft· pool there. By now, later models of the Corsair had been in production and were being sent to the Pacific fleet, while many of the earlier models, such as this airplane, soldiered on in the advanced pilot training role.

[hr4]

F4U Corsair “Whistling Death” Flight Demonstration

[hr4]

Postwar activities appeared routine with assignments at NAS Memphis and the Naval Air Technical Training Center at Pensacola, until 50375 was finally stricken from operational records on April 30, 1946. The airplane was then sent to the NATTC at Norman, Oklahoma, where it remained until it was selected for the Museum collection and routed through Norfolk with other Navy aircraft.

When it came time to take a closer look at this airplane with an eye given to its restoration, it was obvious it had undergone a hard service life. Instead of wounds being acquired in combat, its battle scars were the results of being assigned to aircraft mechanics schools. Dents, gouges, and chips abounded. The interchange of parts was extensive. For example, its fin carried BuNo. 571 01, while the right stabilizer and elevator were marked for BuNo. 50522. Presumably the BuNo. 50375 stenciled on the fuselage and wing panels is the original Bureau Number of this fighter, as records of its transfer from the Navy indicate, for it is very unlikely that these basic components are not original.

It is ironic that such a fearsome and bellicose machine as the F4U should be represented by one which never saw combat. Corsairs were credited for having destroyed 2,140 enemy planes with a loss of only 189 of these “bent-wing” fighters in aerial combat. Japanese pilots feared it more than any other enemy plane in the Southwest Pacific theater of operations. Distinctly marked by its inverted gull-wing, Corsairs were a familiar sight over Guadalcanal, Bougainville, Rabaul, Tarawa, lwo Jima, Peleliu, Okinawa, and Japan. Designed as a carrier based fighter, they served initially from shore based installations on a variety of Pacific islands where in a very short time they became synonymous with Marine Corps Aviation. More importantly, they were the first Navy fighters capable of carrying a bomb load commensurate with those hauled by heavier two-man dive-bombers, and because of this ability, they accelerated the passing of the old dive-bomber.

It is from the events surrounding the Corsair as a Marine fighter that the Museum’s F4U-1D restoration marking scheme was based. In all restorations of this nature, one photograph is selected and scrupulously adhered to, down through the fine degree of details for its paining and marking. In the case of this Corsair, the selection of Operational Marine photographs with clear details from which to choose was rather limited. Narrowing the selection even further, the Corsair had to be a F4U-1D, and one that did not depict an airplane identified with a specific well-known combat pilot. To have done so would be stretching the authenticity of this restoration beyond Museum policy. However, one photograph in particular filled all these requirements. This was ship number 54, carrying a name typical of the type that adorned the sides G>f many American combat planes. The Corsair pictured was assigned to Marine Fighter Squadron VMF-113, operating in the Pacific theater. After the history of the unit was reviewed, it became obvious that to depict an aircraft of this squadron was ideal, for it was representative of the many Marine Air combat units that served so well in World War II.

VMF-113 was first organized at El Toro Marine Base, California, on January 1, 1943, and formally commissioned the following September 15th. Thirteen days later, the fighter squadron departed the United States aboard the aircraft carrier USS Bunker Hill. They arrived at Ewa on the west side of Pearl Harbor, where they joined Marine Air Group 23. Early in January 1944, the squadron was detached to the 4th Marine Defense Air Wing in the South Pacific, where it was assigned to MAG-31 on January 14. By the end of February, all echelons were reunited and began operations at Engebi in the Marshall Islands. Despite this remoteness from the active battle line, eight of the twelve enemy planes shot down by Marine aviators in the Central Pacific in 1944 were scored by Corsairs of VMF-113. These occurred while escorting U.S. Army B-25 Mitchells on a bombing attack against Ponape Island of the Caroline Group, March 26, 1944.

During the following month, the squadron covered the Ujelang landings and made the longest sustained flight ever recorded by Corsairs under combat conditions up to that time, with three of the planes remaining airborne for nearly ten hours. The monotony of aerial surveillance over the seemingly limitless expanse of ocean, during the strangling operation of enemy supply routes to Wotje, Maloelap, Mille and Jaluit, continued almost unbroken until near the end of June when, on the 27th, during a dive-bombing attack on Wotje, three of the 113’s Corsairs were struck by anti-aircraft fire. Two of the Corsairs and the pilot of one were combat losses.

Marine 1st Lieutenant. Robert H Zehner, who sank with his plane, was hit about 50 feet off the water, did a wing–over, and crashed into the lagoon with the cockpit cover still closed. Capt. George H Franck was more fortunate, although he had some precarious moments in the sea before he was rescued by a destroyer. Before the destroyer arrived, however, a PBY Catalina attempted a landing while a Lockheed PV-1 Ventura silence 50 caliber shore batteries. A huge swell get the PBY, smashed its hull and ripped off its engines, necessitating the rescue of seven men instead of one. Meanwhile, orbiting fighters and the twin-engine Ventura control plane, piloted by Navy Lieut. George King of VB-144, we’re running low on fuel. The rescue destroyer was still 6 miles away but sent a whaleboat to the rescue. It too, was hampered by heavy seas. The Ventura pilot hung on, acting as liaison between the two life rafts and the whaleboat, despite the fact that his fuel tanks all registered in the red. He directed the whaleboat first to the PBY crew, who were rescued, and then to the Corsair pilot, Captain Franck, who was picked up. Lieutenant King then returned his Ventura to Roi Atoll on Kwajalein, landing there with only 11 to 16 gallons of fuel remaining. Had he not carried this mission off skill, daring, and resourcefulness, it is doubtful that any of the seven airmen would have been rescued, and had he cut get any finer, he and his crew would have been forced to ditch.

The “Whistling Devils,” VMF 113 pilots called themselves, were not so lucky in July. On the 18th, returning from an attack Taraoa, Maloelap Island in the Marshals, three pilots and planes were lost in severe weather. But for most, long periods of inaction continued until April 1945, when the ground echelon embarked on the USS Sea Flyer and set out for lLe Shima Island and the bloody Okinawa campaign. The ground echelon went ashore at Le Shima on May 6, and 18 days later the flight echelon arrived. Two days after the pilots landed their Corsairs on the newly carved coral airstrip, they achieved their squadrons first victory in the Ryukus Campaign. Marine Lieutenants Woodberry and Weathersbee shared a Japanese KI 60 “Tony” they caught while on CAP (Combat air patrol) between Izena Shima and Yanaha Shima.

On June 22, the day after Okinawa was secured, VMF-113 made its last scores and brought its tally to 21 enemy planes, 12 of which were shot down in June, and which cost the squadron three pilots. In addition to the loss of the pilots during June, seven were killed and 17 wounded on the night of June 10, when a twin-engined Kawasaki KI 45 “Nick” sneaked into the area, showing the correct identification lights and IFF with the proper code, and dropped a bomb in the 113’s bivouac area. A night fighter liquidated the marauding two–place “Nick” fighter but failed to return after he shot down the enemy plane.

In August, following the end of hostilities, the squadron moved from Le Shima to Okinawa and operated from Chimu Air Field until transferred to Omura Air Base on Kyushu, Japan’s southernmost island. They are they remained as part of the US occupation force until the unit was decommissioned on April 30, 1947.

[hr4]

F4U Corsair Training Film

[hr4]

This is but one unit with this type of history to which a corsair of the kind of that is now on exhibit at the National Air and Space Museum could have been assigned. The important thing is this Museum airplane will survive indefinitely, barring natural or man–made disasters. Why was this aircraft restoration any different from those of other museums, one might ask? After a review of some of the details encountered in the restoration of this Corsair, the reader and restorers of other aircraft should be able to answer this question.

At the museums restoration facility, there are normally four and sometimes five aircraft being restored and preserved at any one time. Two technicians are assigned to each aircraft to see the project through from start to finish. Other specialists are available for these projects is required, such as a machinist, metalsmith, welder, chemical/metallurgist and others. The shop is equipped primarily for this type of work which reduces the amount of time and others who might do restoration projects must spend in having to improvise special tools, jings, or to prepare facilities to handle certain jobs. Despite these conveniences at hand, 9,315 man-hours were spent on this restoration of the Corsair perhaps more time than was used to build this aircraft initially when mass production lines were functioning at their most efficient pace. The objectives of “making” and “restoring” are quite different, however. Preserving, along with restoring, makes for a very time-consuming and precise undertaking.

To begin the restoration, the aircraft was disassembled to as many subcomponents as possible. This not only facilitated ease in cleaning, but also allowed these components to be repositioned easily in order to give the technicians better access to the work area and therefore simplify repair. Special jigs or dollies were adopted to hold the larger parts such as the wings and engine. Due to the large size of this airplane, the landing gears were left in place in order to support the fuselage except for the short time they were individually removed for cleaning and preserving.

Many photographs were taken of the cockpit so that they could be used as reference while replacing the hundreds of parts that had to be removed from that comparatively small area for thorough cleaning. This also facilitated a good cleaning and a complete chemical treatment of the inside area of the cockpit and adjacent parts of the fuselage.

Each major component of the airplane, such as fuselage, wings, and control surfaces, were taken separately to the wash rack where the preservation bath process really begins. There are three major steps that are taken in the preservation of airplane components. They are cleaning, which also helps the technicians in restoring the structure, chemical treatment, to remove corrosion and inhibit future deterioration, and protection, which shields the structure for the future from outside elements. Protection is usually surface painting or coating, of both the inside and outside of the structure. Two of these major steps are the responsibility of two assigned technicians in the chemical processing section of the restoration shop.

The chemical treatment process makes the difference between truly preserving an aircraft for museum longevity and lesser restoration efforts that only remove the visible rust and corrosion before painting over this still active deterioration. Modern chemicals can penetrate and protectively coat areas of corrosion that cannot otherwise be reached. For instance, consider the inside wing surfaces at the trailing edge or the skin at the mating points of ribs and formers.Without arresting this hidden corrosion and applying an inhibitor to prevent future deterioration, in time, the airplane will be like so many vintage cars with a nice exterior finish, hiding the fact that their metal structure is being eaten away from the inside. To reach these hidden areas of aircraft structures, it is often necessary to remove some of the skin paneling by drilling out rivets and replacing them later with duplicates.

The cleaning phase included several methods for reaching the metal surfaces for preservation treatment. Oily surfaces were cleaned with solvents such as varsol and trichoroethane, and exhaust stains were removed with Magnusol 728.

Special care is always given in the use of paint and rust strippers, and aluminum brighteners. These chemicals, if left behind in crevices or allowed to act too long, can cause irreparable damage. Only careful study and painstaking experience can prevent this damage from occurring. After chemically cleaning both ferrous and nonferrous metals, heavily pitted areas were cleaned by hand brushing, using steel or aluminum wool, or blasting with glass beads or walnut shells. On this Corsair, none of the metal was deteriorated to the point that some of the sections had to be cut away to eliminate all traces of active corrosion buildup.

The chemical treatment process is perhaps the most important operation in the preservation of these aircraft. Surface coatings for metal that were produced by chemical action can be duplicated as nearly as possible to that of the original surface. This forms a protection against corrosion as well as serving as a base for organic finishes. Corrosion and rust, the latter being a form of corrosion in iron and steel, is a deadly, relentless enemy of metal aircraft. No matter how excellent the quality of paint that is used, corrosion ca:n form between the paint and the metal unless protected by a conversion coating. A smooth appearing metal surface is actually a series of microscopic peaks and valleys which are electrically anodic and cathodic in relation to each other. When moisture is present, these pair up to form electrolytic cells and, like any battery, this release of energy is a process of deterioration. This is why aircraft exhibited outdoors will not survive for long periods, no matter how frequently their exteriors are painted, for with some paints, alkalis form certain metallic soaps that effect the adhesion between paint and metal and create even further damage.

To prevent this deteriorating action, a layer of phosphate crystals was sprayed over the entire structure of the chemically cleaned aircraft, inside as well as out, which neutralized the electrical difference. This conversion coating also served as an excellent surface for holding the new paint to the metal.

The Museum is still experimenting and always learning in this field of extending aircraft life through chemical processes, and it appears that each newly restored aircraft is preserved better than the last. Dependency upon chemical treatment has become so important at the National Air and Space Museum that the processing of every metal part of an airplane is an absolute must, and not just merely to be rubbed clean of visible rust or corrosion.

[hr4]

F4U Corsair Restoration Project

[hr4]

The third step of our preservation process is protection, which is done in the painting phase by the two technicians assigned to the Corsair restoration. The painting on the outside of the airplane was an obvious requirement for camouflage colors. But the inside surfaces, not ordinarily painted by the manufacturer, were given a protective coating of Clear Coat, a product of Okite, which has been found to work well over the years. Like most Navy aircraft, the Corsair survived for as long as it did due to BuAir specified interior paint at the time of manufacture.

That takes care of the airframe, but what of the engine?

Cleaning, preserving and restoring the Pratt & Whitney R-2800 was no minor task. It was totally disassembled and each part preserved for lasting protection. In some of the Museum’s earlier restorations, especially those having World War II engines, the insides of cylinders would merely be checked with a baroscope,and if rust or corrosion were not apparent, their interior walls were sprayed with Soft Seal for protection, and their outside appropriately painted for the restoration. Since that time, this practice has been changed for good reason.

In one such engine, there was only one minor trace of rust that was detected on the inside wall of one of the cylinders. Everything else seemed in good condition. It was decided to open the engine just to make sure, and it was fortunate that this happened. Many magnesium parts were in a very corroded state on the inside and in a location where they could not be seen through the baroscope. Three cylinder bases were also rusted. While lubricating oils serve as a good preservative up to a point, stronger measures have to be taken for long-term preservation. Engines are now completely torn down for each aircraft being restored, regardless of their apparent condition. When reassembled, each part is coated with CRC Soft Seal, thinned with CRC 3-36 so that it can be sprayed. After drying, this material will not run, yet if the pistons are moved, for repositioning the propeller for instance, it will not be fully scraped away from the cylinder wall and will maintain a protective coating.

After the engine is reassembled, all openings are sealed to prevent moisture and foreign objects from entering. One example of this process is in the making of new exhaust gaskets, leaving their centers closed for a seal.

While the cleaning and preserving of the metal structures was taking place, a literal world-wide search was conducted for Corsair parts, for there were far more missing parts than first anticipated. This Corsair, for instance, had a carrier type hard rubber tail wheel for carrier deck landings, but no arresting hook. Either an air tire and wheel for runways, or a carrier arresting hook had to be obtained. A Marine Corps Major, who was gathering parts for his own Corsair, gave an extra tail hook to the Museum, along with several missing fuel control lines. Replacement main tires came from a warbird owner in Arkansas, and an ad in Trade-a-Plane for a new canopy to replace the broken one was answered by a man in North Carolina. Engine parts came from Canada and an air museum in Michigan. The throttle quadrant, interior and exterior lights, and many of the special cockpit switches were flown in from New Zealand aboard visiting R.N.Z.A.F. Lockheed C-130s. These parts were obtained from wrecked Corsairs that were retrieved from the Pacific war zone.

The list goes on of other parts received from other museums and private donors. For the most part, the Corsair is complete, but a list is maintained for the few parts unique to the F4U that are still needed, and the search continues. Among these items are: an oxygen bottle to be at the right of the pilot’s seat, plotting board and associated light which is to be attached to the instrument panel, APX-1 (IFF) and cockpit control head, fairing for left outboard flap hinge (inside face) and rear fairing for left side, center flap hinge (outboard face).

The Vought F4U-1 D is unusual for it is a mix of manufacturing techniques ranging from the very newest in the state of the art at the time of manufacture, to some of the oldest practices. The fuselage, for example, utilized the new technique at that time of spot welding large, uninterrupted skin plates instead of using the practice of flush-head rivets and smaller size skin panels. The wing, on the other hand, had the rear half covered with fabric. All other contemporary fighters at the time were fully metal covered except for flight controls. This did change with later models of the Corsair. The ailerons were constructed of wood and covered with plywood, while elevators and rudder remained fabric covered.

The question is often asked if restored aircraft of the National Air and Space Museum will fly. The fact of their airworthiness has already been established and, therefore, there is no Museum requirement for additional flying . However, the purpose of the collection is to document aviation technology by preserving actual specimens, therefore it is a policy of the Museum that its airplanes will not be flown.

Were these airplanes to be in flyable condition, their engines would not have the preservative coating that they now have on their interiors. Should it ever become necessary to run these engines, the preservative material can be removed and replaced with proper lubricants. Aircraft electrical components and hydraulic systems are kept original and preserved in a restored condition. If the airplane were to be safely flown, many of these aged components would have to be replaced with new hydraulic seals and flexible hoses, as example, and would therefore be made from modern technology materials and fabrication methods, and would no longer be preserving originality. Structures that may have been weakened through age or internal damage would have to be strengthened for flight which also would alter the original design. These are a few of the important reasons why ·these airplanes are not flown, but are as technologically complete as a flyable airplane should be.

When the long awaited day of the rollout of the finished Corsair arrived for outdoor photographs, it was a day marked by smiles upon the faces of all who had a part in this project. By coincidence, this occurred on the same day that Marine fighter ace “Pappy” Boyington was scheduled to speak at the Museum about his experiences as commander of the Black Sheep Squadron in the Pacific with Corsair fighters. More than the usual number of cameras were on hand for this roll-out, since “Pappy” was also on hand. With affection that could not be hidden as he laid his hand on the side of the gleaming fuselage, his first remark was: “The Corsairs that I flew never looked as good as this one!”