By Carroll R. Anderson, in the May 1988 edition of Airpower

Editor’s Note: Wings & Airpower have published a multitude of articles on the Lockheed P-38 Lightning, including a well received 13 part series that established an authenticated body of information about this famous, but often misunderstood aircraft.

The twin engined P-38 was unique for its time and was the only highly successful twin engined, single seat fighter of its era to see both mass production and utilization. It served as a fighter, a bomber and a reconnaissance machine. Its firepower was devastating. It was even longer ranging than the P-51 Mustang, and when utilized correctly, was difficult to beat in aerial combat. In fact, the P-38 became the model for combat aircraft of the future, which utilized speed, altitude capability and firepower to defeat more maneuverable opponents.

The twin engined P-38 was unique for its time and was the only highly successful twin engined, single seat fighter of its era to see both mass production and utilization. It served as a fighter, a bomber and a reconnaissance machine. Its firepower was devastating. It was even longer ranging than the P-51 Mustang, and when utilized correctly, was difficult to beat in aerial combat. In fact, the P-38 became the model for combat aircraft of the future, which utilized speed, altitude capability and firepower to defeat more maneuverable opponents.

As long as the P-38 pilot kept alert, entered combat at high speed and then pulled away to resume the contest on terms of his own choosing, he was difficult to bring down. His aircraft’s unusually long endurance, up to 2,600 miles with tanks, allowed him time to make repeated passes, and its firepower of one 20mm cannon and four .50 caliber machine guns, all of it mounted in the nose, put out a lethal amount of high velocity shells. The only way a P-38 pilot could be defeated – and it happened all too frequently – was if he disregarded the warning never to dogfight with opponents, thereby ending up in a turning contest which lost him speed and altitude.

In the Pacific, Japanese pilots would deliberately slow their aircraft down, inviting P-38 pilots to turn with them, often pulling up into a slow climb that set up a pursuing P-38. Concentrating on the kill, the American pilot would deprive himself of the speed edge the P-38 required and while the P-38 turned slowly, tracking its quarry, often at low altitude, the aircraft would lose its advantage. Its lighter opponent with a wing loading far less than that of its bigger rival, would quickly flip into a loop and would be on the P-38’s twin tails within seconds. Shorn of his speed, the P-38 pilot would wallow around trying to regain it. If the enemy’s aim was poor, he might just be able to do it. The P-38 could absorb a great deal of punishment and once speed was again built up, it could outrun the opposition; but during that time a P-38 pilot had attempted to maneuver with his lighter opponent, he was at the mercy of the enemy, for it required too much time for a P-38 to get into its turn, even with hydraulic boost on its ailerons. Once in a turn, the P-38 came around fast, but by that time the enemy was rolling out in the opposite direction. On the other hand the P-38 could move through the vertical, up and down, very quickly, making it an excellent platform for diving and then climbing back up. Adding to this was its solid ride and stability, which also made it a near perfect gun platform. Utilized to its best abilities, it was almost unbeatable in the Pacific and it was in P-38s that America’s leading WW II fighter aces were made.

In spite of the awesome array of gauges and dials in the cockpit of the Lockheed P-38, the basic instruments were easily located. Further, the various handles, knobs and gadgets required for landing gear, flaps, etc., came easily to hand, although post war criticism of the Lightning cockpit has run the gamut from condemnation of the fuel crossfeed system to cockpit heating, and to the fact that the flap handle was located on the right side of the cockpit requiring a deal of ambidexterity alien to some fighter pilots.

In the Southwest Pacific area, we seldom flew high enough to become critical of the heating system, and we must have learned our other lessons well for no one – as far as I knew – ever had a problem with the fuel feed system or with handling the flap handle in the middle of a peel off while transitioning from a buzz job speed of near 300 mph to 150 mph at the top of the maneuver.

Once the rudder pedal lock releases had been kicked loose and the pedals adjusted, an absolute necessity for me if my tentmate Lt. Sammy Morrison had previously flown the aircraft, for he was the smallest pilot in the 433rd, it simply was a matter of adjusting the seat height and buckling up, a task in which I was assisted by my crewchief, Sgt. Thomas Ruiz from Santa Fe, New Mexico.

The canopy was dropped and safety locked, right window cranked up, and now it was a matter of waiting until Major Warren R. Lewis’s P-38 engines began energizing.

- Trim tabs were properly set with a bit of up on the elevators.

- Mixture controls; idle cut-off.

- Switches on.

- Fuel tanks on reserve.

- Belly tank drop switches on.

- Fuel boost on.

- Reach down and unlock primer.

- Twist to left and give cold engine two shots of prime.

- Lock primer.

- Energize left engine until steady pitch sound is heard, then engage.

Remarkably there seldom was a failure to start because of not enough or too much priming. The Allison would belch a glob of smoke and then rumble into action. Forward on the mixture control, and watch the oil pressure · and coolant gauges. Repeat the procedure for the right engine, then make sure the booster pumps were functioning.

Yoke backwards and forwards while observing the elevators, at the same time double-checking that the correct amount of up trim tab is clearly visisble. Sometimes the previous pilot would use a considerable amount of tab to relieve the back pressure on the yoke during landing, and then forget to trim-back to neutral. If you didn’t check for this you not only left the ground as if riding an elevator, but found yourself applying forward pressure on the stick while wondering what had happened to cause such an abrupt upward leap. Now check aileron travel visually. Check flap travel. Check each left and right mag on each engine. Cycle each prop a couple of times. Drop Fowler flaps to takeoff position. One last check of the gauges. Radio on and set to proper channel. You’re ready.

The best description of the sound made by the Allison engines was to simply say that they “galloped,” and every P-38 pilot recognizes that sound without having to look toward the airplane making it. When power was added to swing out onto the runway for takeoff, the noise became a canned rumble.

The best description of the sound made by the Allison engines was to simply say that they “galloped,” and every P-38 pilot recognizes that sound without having to look toward the airplane making it. When power was added to swing out onto the runway for takeoff, the noise became a canned rumble.

Taxiing out, the hydraulic brakes required constant pumping to keep up pressure, which accounted for the bobbing action Of the pilot’s upper body undulating in time with the nose of the aircraft. Once in position on the runway with the brakes set, power was advanced to approximately forty-five inches. When your flight leader or element leader rocked his ailerons, you knew it was time to go, and that moment occurred precisely when the nose of the leading P-38 kicked upward as the leader released his brakes.

Taking off in formation was a cinch in the P-38 because the big airplane tracked perfectly. Even at 11 tons gross, we could get off in 4,000 feet. A slight throttle adjustment would immediately rectify any movement to the left or right. When the flight leader lifted off at about 120 miles per hour, with a full combat load, his wingman lifted off as well. In the J models, everyone held down the nose to build up to single engine speed, which was near 150 miles per hour and, of course, the gear was retracted immediately. The takeoff flaps were milked up quickly as well, because no one wanted any more drag than necessary in the event an engine died requiring single engine procedure.

I was witness to only one engine failure on takeoff during the entire time I flew P-38s and that was when Lt. Wilson Ekdahl of the 431st went thump in the stumps at the end of the runway at Soroka Strip on Biak Island, one degree south of the Equator, off northwestern New Guinea. Wilson was trying for a takeoff a second time after one engine had warned him previously by stopping on the first takeoff run. Amazingly, he escaped unhurt. When the explosion, flying chunks of P-38 and confusion settled down, Wilson was hiding behind a huge piece of coral while officers and enlisted men searching the relatively undamaged cockpit cursed and swore over their inability to locate the body. Ekdahl was no fool. He wasn’t going to hang around the remains, especially when there was a 1,000 pound demolition bomb about to “cook-off.” He was still safe behind the rock when the bomb went off and drove everyone else to ground.

Climbing out at about 160 miles per hour, we switched to a belly tank and hit the crossfeed button. Assured of proper flow, we turn off the boost pumps and set in the props _rpms for an extended climb. Cruise was peformed at slow speeds in the Southwest Pacific, especially after Charles Lindbergh had taught us best cruise performance. The missions became longer and longer and the distances stretched out to eight and nine hundred miles over the Moluccas and the Banda and Flores Sea.

Back home the 433rd would sweep the strip at Biak about ten to fifteen feet off the ground. Wingmen had to be careful because a sprig of a tree stuck up in the revetment area, and while no one ever hit it, it was certainly an unpleasant surprise to look back from an element leader and see that runt of a tree about to be engaged head on.

Our CO, Warren Lewis, demanded tightly grouped landings. He wanted to look back and see an airplane on the 4,000 ft. runway as he turned off, with another about to touch down and another flaring to land . We did this for him again and again, if for no other reason that to put on a show for our enlisted personnel, allowing them to see a fine performance each time their Lightnings came home from a mission.

The big bird would zoom to several thousand feet on the peeloff, if you let it, but with flat pitch already established, retarded throttles would slow it rapidly to near 150 mph, where the pilot would drop the gear, check the gauges and handpump to make sure the gear was down, then crack half flaps and pull the nose around toward the runway while cranking in sufficient upelevator trim to take some of the load off the yoke. Crossing the end of the field still pulling about 16 inches of mercury at 110 mph, he would chop the throttles, holding back on the yoke for a full stall landing at near 85 mph. If the landing was performed right, the nose wheel would not touch until considerable forward speed was lost. With the wind up in the air, ground effect helped slow down the Lightning, then it was pump the brakes like hell and turn off midway down the runway, if possible. Pull back the mixture controls. Turn everything to off, and tell the crew chief it flew beautifully, which it usually did.

Photo Captions

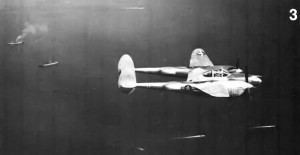

- P-38J flown by Captain Frederick Champlin of the 475th Fighter Gp., 431 st Fighter Sqdn., over Leyte Gulf. Champlin was an ace with nine official victories. but what makes this photograph Interesting Is that Champlin Is flying No. 126, an aircraft that was usually flown by Bill Gronemeyer. an Instructor check pilot at the Combat Replacement Training Center at Nadzab, northeastern New Guinea. Gronemeyer was killed while Instructing an Australian pilot In a twoseat P-38. Champlin was flying No. 126, Gronemeyer’s regular plane, because his aircraft No. 112 was previously lost when flown by Major Thomas B. McGuire, CO of the 431st Fighter Sqdn., one of the war’s premier aces with 38 victories. McGuire had gone to the aid of a novice pilot during low level combat against a Japanese Zero over Los Negros Island In the Philippines. It had begun as a routine training mission; McGuire and another experienced fighter pilot had been breaking In two newly arrived pilots. The Zero. said to be flown by Sholchl Suglta. a Japanese ace with at least 70 victories to his credit. made a quick pass and shot down one of the new men. At 1.500 feet. with his drop tanks still attached. McGuire attempted to turn too tightly as he sought to drive Suglta off the tall of the second novice. In doing so, McGuire broke a cardinal rule he had often repeated to his command: Always drop your tanks before entering cornball As McGuire put his P-381nto a tight vertical turn, the elevators became unresponsive and he began to mush. as G forces on the partially emptied drop tanks forced the still considerable weight of their fuel to the rear. The center of pressure swiftly moved aft and. at low speed. the elevators did not respond. Down to a few hundred feet In a tight turn. McGuire could not recover and aerial combat claimed another victim when he spun Into the ground. Similar to the P-38J, the P-38L had V-171 0 Allison engines which offered 1.475 hp for takeoff. with war emergency horsepower of 1,600 at 26.500 feet. It was also the first to be equipped with underwlng rocket trees for launching ten .5-lnch projectiles. A total of 3,914 were completed, all but 113 by Lockheed. Aircraft can usually be distinguished by Its deeper “beard” radiators. which differ from the more evenly tapered Installations of Its predecessors. In the L model. P-38 reached a top speed of 414 mph.

- The 431st Fighter Sqdn. over Huon Gulf. near Lae, New Guinea, In April. 1944, In typical attack formation. It Is led by Col. Charles MacDonald. CO of the 475th Fighter Gp., “Satan’s Angels,” an ace with 27 victories. MacDonald began the war as a lieutenant stationed at Wheeler Field. Hawaii. and was present during the Japanese attack of December 7th. Photo was taken from tall turret of a B-25, whose pilot was going so fast that the other two fighter squadrons In the group, the 432nd and 433rd, never were able to catch up and have their pictures taken.

- Early P-38s are shown over California. France’s Army of the Air was so impressed by Lockheed’s new fighter that it ordered 500 of them in 1940. In an era when “destroyer” or heavy fighters, such as the Me-110, etc. were looked upon as the “heavy cavalry” of the sky, particularly for low level work, the P-38 seemed tallor-made. But it was the turbosupercharged P-38 built for high altitude performance that proved the big fighter’s worth. Unfortunately for early Lightnings, shortages of superchargers kept that important addition off the engines of the Initial production runs and when the British tested their first export P-3Bs, Models 322-16s, they did so without supercharging and the results were mediocre. As a result, production orders for the RAF were cancelled.

- P-38H with tapered nacelles. These began delivery in March, 1943, and had more powerful 1,426 hp engines, improved 20mm cannon and supercharging for better performance at altitude. Note mass balance horn on elevator between fins, first installed on YP-38.

- P-38J over Leyte Gulf. Despite its sterling characteristics, the P-38 was used mainly by the USAF. with only a handful flown by Chinese, French and Australian units. Ironically, one of the few foreign pilots to lose his life in a P-38, was the legendary Antoine de Saint Exupery, who was flying a photoreconnaissance F-5 Lightning over southern France, when he was killed on July 31. 1944.

- The author-poet is shown taxiing his Lightning at its base on Corsica.