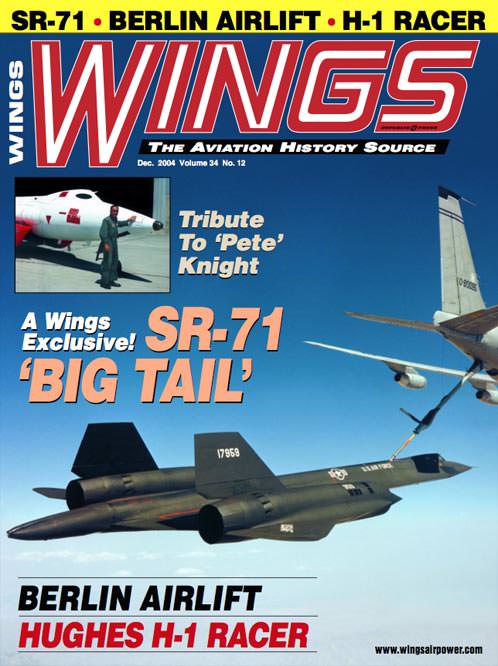

By Tony Landis, in the December 2004 edition of Wings

Shortly after the first SR-71s began flying operational missions over North Vietnam, the Air Force began looking into ways of expanding the capabilities of this exotic aircraft. With its versatile interchangeable noses, mission planners would have to make a choice of flying either optical cameras or side-looking radar, depending upon such factors as mission requirements and weather over the target area. Unfortunately several missions were rendered useless at the last minute when weather over the target prevented use of the optical camera systems installed. There was also the possible threat that future ground defenses would someday have the ability to reach the SR-71 from behind since it carried no aft facing defensive countermeasures.

In 1974, the Air Force identified a requirement for an aft facing Electronic Countermeasures (ECM) capability for the SR-71, and several feasibility studies examined by the Air Force included conformal packages underneath the aft fuselage and belly pods, as well as an extended tail fairing. After researching all the possibilities, the extended tail appeared to be the most viable option based on lowest cost, added volume and least amount of aerodynamic drag. The new ‘Big Tail’ assembly would be 13 feet 9 inches long and weigh 1,273 lbs. with 49 cubic feet of space to carry 864 lbs. of payload. The primary payload would consist of aft-facing ECM as well as the 24-inch Optical Bar Camera. Because of the lengthened tail section, the new assembly would also have to be articulated to move 8.5 degrees upward in order to clear the runway during take-off and landing and then downward so it would not interfere with the aircraft’s drag chute deployment on rollout.

The tenth SR-71 built (61-7959) was selected to receive the new modification. This aircraft had been delivered to Palmdale in late-1974 to become part of the Blackbird flight test fleet, and after all necessary modifications and upgrades ‘959 made its first test flight as the ‘Big Tail’ on December 20, 1974. Once the final decision had been made to proceed with the Big Tail modification, this airframe was chosen so there would be no effect on the operational fleet, and ‘959 was then modified with the new tail fairing between April and November of 1975. Necessary structural modifications included a 51-inch adapter unit for the new tail, air conditioning for cameras and other equipment, as well as re-routing the fuel vent along the upper surface of the tail. In addition to all the tail modifications, chine bays in the aircraft’s forward fuselage were modified to accommodate the 24-inch Optical Bar Camera.

Once the required stress and vibration testing was complete, Big Tail was taken out for its first high-speed taxi test on November 20, 1975 by Lockheed test crew Darrell Greenamyer (pilot) and Steven Belgeau (RSO). The crew took the aircraft up to 110 KIAS and performed tail movement and parachute deployment tests. With everything functioning as planned Big Tail was now ready to begin flight testing. Two weeks later, on December 3rd, the same crew took ‘959 up on its first flight. Lasting just over one hour, the crew performed basic flight checks as well as tail deflections and fuel dump tests. This flight was kept to an altitude of 29,000 ft. and was flown subsonic the whole time.

These are just a sample of the HUNDREDS of images on the SR-71 Blackbird Special Edition CD

The first supersonic flight took place during flight no. 2 on December 11, and the tail remained in the upward position for the entire flight. With each test mission flown by the same Lockheed crew, Big Tail was taken to higher speeds and altitudes finally achieving Mach 3 speeds at 75,000 ft. during flight no. 6 on January 28, 1976. Prior to turning the aircraft over to Air Force flight test crews, Greenamyer performed four solo flights (pilot only) to prove the system could be run by just a single crew member, with the RSO’s seat occupied by a ballast dummy affectionately known as ‘Sierra Sam’. During two of these test flights on March 3 and March 10 the tail failed to operate automatically and had to be faired manually inflight by Greenamyer.

Once Lockheed crews had proven the system worked, operational flight testing was taken over by the Air Force. Tom Pugh and Bob Riedenauer were the pilots and RSO duties went to William Frazier and John Carnochan. Over the next six months these dedicated Air Force crews made 23 flights in Big Tail testing various camera systems in the extended tail and chine bays, as well as new ECM systems such as the DEF I, DEF J and DEF A2. The first Air Force flight took place on May 5, 1976 with Pugh and Carnochan taking ‘959 out to Mach 3.0 at an altitude of 77,300 ft. The next flight on June 18 was the first to test out the 24-inch Optical Bar Cameras in the chine bays and was flown subsonic for the entire flight due to a late takeoff which adversely affected their tanker rendezvous and thus limited ultimate fuel load.

During July, two missions were flown against McDonnell F-4 Phantoms to test out some of the new DEF A2 and DEF J CM systems onboard, and in October two missions were flown with a total of four Optical Bar Cameras installed, one each in the aircraft’s nose, tail and chine bays. One of the more exciting flights occurred on October 15th with Riedenauer and Carnochan as crew when the drag chute deployed during a low pass over Edwards AFB, but fortunately, the aircraft was able to return to Palmdale without further incident. An unexpected benefit of the Big Tail modification was that the pilot could actually trim the aircraft by simply adjusting the position of the tail.

Although Big Tail had proven to be a viable system operationally, the Air Force chose not to pursue the concept any further. After only 36 flights with the extended tail,’959 made its last flight on October 29, 1976 with Pugh and Frazier taking it out to Mach 3.2 at 76,600 ft. to test the DEF I shroud, four OBC cameras and the newest onboard navigation systems. After this flight ‘Big Tail’ was simply placed in outdoor storage at Palmdale. Though it had only 866 hours of total flight time and 304 flights to its credit, ‘959 was grounded and then used as a valuable source of spare parts for other flight test SR-71s. It was finally disassembled by World Wide Aircraft Recovery and moved by truck to the Air Force Armament Museum at Eglin AFB, Florida in the fall of 1991 where it is proudly displayed to this day.